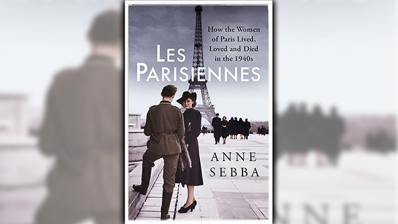

Stephanie Jones: Book Review - Les Parisiennes by Anne Sebba

- Publish date

- Thursday, 25 Aug 2016, 11:17AM

It was not until a speech by President Jacques Chirac in 1995 that the ugly truth French people had known for decades was finally spoken aloud, and apologized for, by the state: the round-up, or rafle, of more than 13,000 of Jews in France for deportation to Third Reich camps in eastern Europe was achieved with the complicity and deliberate assistance of the French authorities. Before being transferred east, those arrested were held in central Paris’s Vélodrome d’Hiver, the bicycle stadium that was never intended to be a resting post for terrified prisoners, and where food and water supplies and sanitary facilities were wholly inadequate.

As Anne Sebba writes in Les Parisiennes, an important social and political history of women in 1940s Paris, one of the young nurses attending those at the Vel d’Hiv was so traumatized by what she saw that she was never able to talk about it. Fortunately for us, Sebba’s book is rife with the voices of articulate women, many of whom are speaking in the 21st century. One, at the time of publication, is the president of the ADIR, the survivors’ group of deportees and internees of the resistance which helped fund the medical treatment and convalescence of many hundreds of women in the years after the war.

That women continue to make themselves heard is not incidental. France’s relationship with its own history is vexed. Visiting Vichy, the spa town which became government headquarters when France fell in 1940, Sebba found the young staff at the Tourist Information Office appeared to know nothing of that period of their town’s history. Were they so inclined, Les Parisiennes fills in many gaps, its chronological structure beginning with misplaced French confidence, in 1939, that the Maginot Line would hold against any German advancement, leaving France unaffected by events occurring elsewhere in Europe.

Then came occupation, and the abandonment of Paris by nearly three million of its five million citizens. Though Sebba leaves the subject of motherhood largely unaddressed, the issue of sexual collaboration with occupying Germans remains difficult to this day. By mid-1943, almost 80,000 women in the occupied zone of France were claiming child support from Germans. Most of these children were the result of consensual liaisons, but post-liberation, thousands of women returning to Paris from the Ravensbruck concentration camp and other centres fell victim to marauding Soviet soldiers. That all were severely undernourished and many desperately ill, Sebba reports, made no difference. One returnee said it was only the open ulcers on her skin that spared her.

The resistance organized early. Sebba does not argue that it was a women’s movement but proves that the women of Paris were essential to its success, often using their innocuous cover as office workers and stay-at-home mothers to subvert Nazi actions. Though one-third of Jews in France at the start of the war fell victim to the Holocaust, 90% of Jewish children survived, thanks to “a vast network of French well-wishers” who risked their lives to hide them. Women were at the centre of this network. Commerce offered plenty of cover, and one resistance agent used her legitimate role as the public relations director for a Paris couturier to turn the office into a secret courier depot for the resistance, under the noses of the German officers’ wives who frequented the grande maison.

Through it all, Paris remained a siren. Though the Louvre had been mostly emptied of its treasures in anticipation of bombing, Hitler – who wanted German soldiers to experience the pleasures of Paris – headed straight for the museum during his only visit to the city, in June 1940, in service of his aim to expropriate French culture.

Sebba’s lens is panoramic yet focused, and it zooms right up to one of the thorniest controversies of the war’s aftermath in France. While soldiers and known resisters who evaded capture are celebrated, victimhood is seen as shameful, and political prisoners and captured Jews are in this category. With liberation came a gendered response and “the simplistic notion that the women had collaborated while the men had fought”. The accounts of Ravensbruck survivors were often met with disbelief, even by their own families.

Sebba notes that very few histories of the period acknowledged the experiences of the several thousand French political prisoners. Conversely, no reader can leave Les Parisiennes in any doubt as to how thousands of Parisian women applied their wits, courage and intelligence to the matter of survival and the protection of others, or how Paris and its people willfully resurged and constructed a new future.

Take your Radio, Podcasts and Music with you